What is net migration and how have the numbers changed?

For many years, the number of people coming to the UK has been higher than number of people leaving.

Net migration to the UK reached record levels in 2023 but has since started to fall, driven by a drop in the number of family members coming on study visas along with fewer arrivals on resettlement schemes.

Here the PA news agency looks at the latest available figures on net migration and how they have changed in recent years.

– What is net migration?

It is the difference between the number of people coming to live in the UK long term and the number of people leaving to live in another country.

For many years, the level of immigration – people coming to the UK – has been higher than the level of emigration – people leaving.

This means net migration is a positive number – in other words, more people are coming to settle in the the UK than are leaving to settle in another country.

– What are the latest figures for net migration?

Estimated net migration to the UK stood at a provisional total of 728,000 in the year to June 2024, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Some 1,207,000 people were estimated to have immigrated to the UK during these 12 months, while 479,000 were estimated to have emigrated, making a net migration figure of 728,000.

This is down 20% from a record 906,000 in the previous 12 months for the year to June 2023.

– How has net migration changed in recent years?

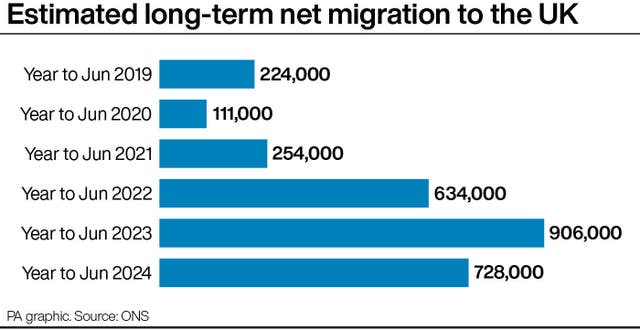

The figure was broadly flat immediately before the Covid-19 pandemic, standing at 216,000 in the year to June 2018 and 224,000 in the year to June 2019.

It then dropped to an estimated 111,000 in the year to June 2020 when restrictions introduced during the pandemic limited travel and movement.

The total rose to 254,000 in the year to June 2021, followed by steep jumps to 634,000 in the year to June 2022 and 906,000 in the year to June 2023.

The latest available figure of 728,000 for the 12 months to June 2024 suggests levels are starting to decrease.

– What caused net migration to rise to record levels?

Several factors were behind the recent increase.

The war in Ukraine led to thousands of people from that country coming to live in the UK through the Government’s resettlement schemes.

A similar scheme has seen British nationals arriving in the UK from Hong Kong, fleeing the security crackdown by the Chinese government.

“Pent-up demand for study-related immigration because of travel restrictions during the coronavirus pandemic also had an impact,” according to ONS director of population statistics Mary Gregory.

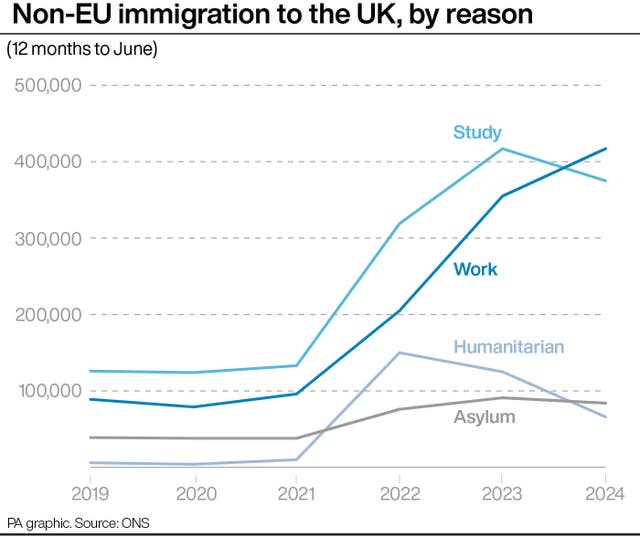

The number of people coming to the UK from outside the EU to study rose from 133,000 in the year to June 2021 to 319,000 in the year to June 2022 and then 417,000 in the year to June 2023, before falling to an estimated 375,000 in the year to June 2024.

A further factor has been the changes to the UK’s immigration system after Brexit.

“Instead of migration to the UK being driven by EU+ nationals (EU+ comprises EU countries plus Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Switzerland), we’re now seeing more people from further afield, especially Indian, Chinese and Nigerian nationals,” Ms Gregory said.

The post-Brexit introduction of new visas for specific kinds of employment – such as the skilled worker visa and the health and care worker visa – has boosted the number of people immigrating to the UK for work.

Some 417,000 non-EU+ nationals arrived to live in the UK in the year to June 2024 for work-related reasons, up from 355,000 in the previous 12 months and 205,000 in the year to June 2022.

– What caused net migration to fall in the latest figures?

The 20% drop from 906,000 in the year to June 2023 to 728,000 in the year to June 2024 was driven mainly by a fall in the number of dependants, or family members, arriving in the UK on study visas from non-EU+ countries.

This is likely to reflect changes in migration rules introduced in early 2024 which restricted the ability of most international students to bring family members.

Fewer people are now arriving in the UK through the Ukraine and Hong Kong resettlement schemes.

There has also been a rise in long-term emigration from the UK, due to an increase in the number of students who originally came on study-related visas and who are now reaching the end of their courses.

– How has the mix of nationalities changed?

Non-EU+ nationals accounted for nearly 86% of total long-term immigration in the year to June 2024, while EU+ nationals made up almost 10% and British nationals nearly 5%.

This is a major change from the pattern before the UK left the European Union and before the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the year to June 2019, non-EU+ nationals accounted for just over 42% of total immigration, while EU+ nationals made up 50% and British nationals 7%.

– How do recent levels of migration compare historically?

The ONS has spent a number of years reforming the way it estimates levels of migration, after the previous method – based mainly on an international passenger survey – was found to be unreliable, particularly in the way it calculated the number of people coming to the UK to study.

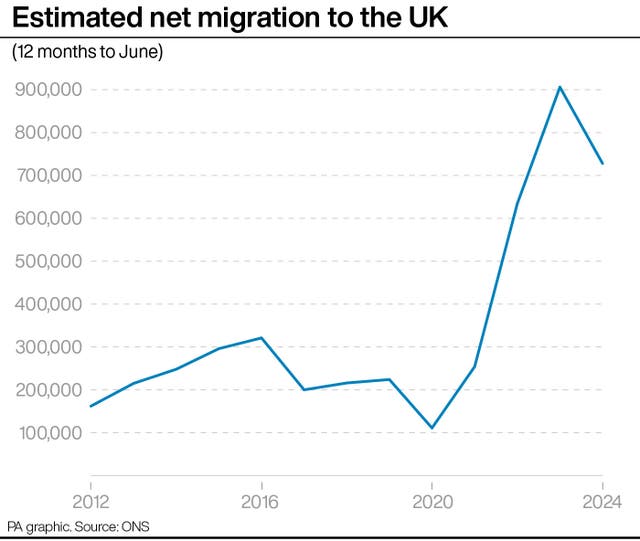

A comparable set of revised and improved figures has been produced by the ONS going back as far as the year ending June 2012, when net migration was estimated to be 162,000.

This figure then rose each year to reach 321,000 in the year to June 2016, before falling back below 300,000 in subsequent years and plunging to 111,000 in the pandemic-affected year to June 2020 – the lowest annual figure in the current time series.

The net migration of 906,000 for the year to June 2023 is the highest annual figure in the time series.