Universities must be more transparent with public money, skills minister says

It comes after reports that two in five universities and colleges in England expect to run at a deficit this year.

Universities have “lost sight” of their responsibility concerning public money and should be more transparent about how it is spent, a Government minister has said.

It comes after revelations that two in five universities and colleges in England expect to run at a deficit this year.

Writing in The Sunday Telegraph, skills minister Baroness Jacqui Smith said universities should focus on “the core mission of higher education, which is rooted here in Britain, its young people, its economy and its society”.

“We ask students to make a considerable investment in their degrees. Universities have huge revenues and must be more transparent about where this money is going,” she said.

“They ask Government to do more to support them, but seem to have lost sight of their responsibility to protect public money.”

Last November, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson announced undergraduate tuition fees in England, which had been frozen at £9,250 since 2017, would rise to £9,535 from 2025/26 to “secure the future of higher education”.

“But we have a clear message to university leaders across the country: you also need to do your bit,” Baroness Smith said.

“If we allow you to increase the fees you can charge students, then this – and the salaries you earn – must be backed with a clear commitment to break down barriers to opportunity and support our mission to drive growth.”

The deterioration in financial performance for the universities sector is likely to continue without reforms, the Office for Students (OfS) has warned.

The higher education regulator said it is making preparations to protect students in case of possible closures of institutions.

The watchdog’s annual health check said 43% of higher education providers in England face a deficit in 2024/25, compared to 40% of institutions in 2023/24.

The OfS analysis said the primary reason for the decline is a fall in international student recruitment and estimated that overseas student numbers could be more than a fifth lower than previous forecasts.

In January, Ms Phillipson said universities would have to demonstrate that they could deliver “best outcomes” for students in the wake of increases in tuition fees.

“We will expect the higher education sector to demonstrate that, in return for the increased investment that we are asking students to make, they deliver the very best outcomes,” she said.

Ms Phillipson said she expected universities to play a bigger civic role in their communities and make a “stronger contribution” to economic growth.

University leaders have been warning of significant financial concerns caused by a drop in the number of overseas students, who can be charged higher tuition fees, following restrictions introduced by the former Conservative government, as well as frozen tuition fees paid by domestic students.

A number of institutions across the UK have announced redundancies and course closures over the past year as a result of growing financial pressures.

Philippa Pickford, director of regulation at the OfS, told the media at a briefing: “We’re not expecting short-term university failures, certainly of a large institution, but it is something that we are preparing for and making sure that we’ve got processes in place to manage.”

She said the OfS is working closely with a small number of institutions where they are “concerned about their financial viability” to think about what needs to be put in place to protect students if they were to fail.

Ms Pickford added: “There is no doubt that if it was a large institution that fails, our ability to secure good outcomes for students is quite low, and that’s why we think it’s really important to have some sort of special administration regime in place for higher education.

“I know that’s something that we’re talking to Government about at the moment.”

Some universities are predicting a strengthened financial performance in the longer term, but the OfS has warned that forecasts seem “too ambitious”.

“We are concerned that this expected recovery is based on overly ambitious figures for recruitment growth over this period: 26% growth in UK student entrants and 19.5% growth in international student entrants,” the report said.

Since January 2024, international students in the UK have been banned from bringing dependants with them, apart from some postgraduate research courses or courses with government-funded scholarships.

The OfS report said international student entrant numbers are projected to be 21% lower than last year’s forecasts.

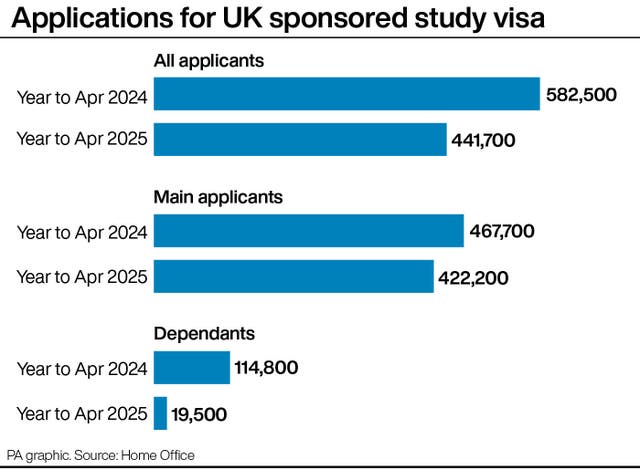

Separate figures, released by the Home Office on Thursday, showed that study visa applications were down 24% in the year to April 2025 compared with the previous 12 months, from 582,500 to 441,700.

The fall has been driven by a steep drop in the number of applications that cover dependants (down 83%), with only a small drop in the number of main applicants (down 10%).

The Government is due to set out its plan for higher education reform in the summer.