Reeves uses first Budget to hike taxes, increase borrowing and boost spending

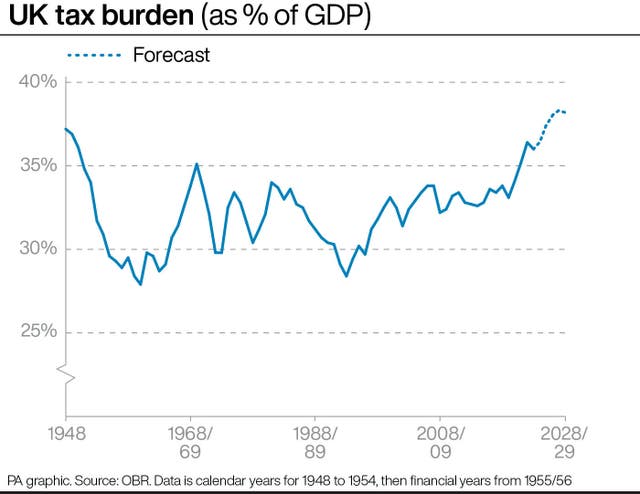

Chancellor Rachel Reeves used Labour’s first budget since 2010 to put extra money into public services but sent taxes to a post-war high.

Rachel Reeves raised taxes to a historic high and sent borrowing soaring as she gambled on increased spending to boost growth and repair public services.

The Chancellor used her first Budget to announce £40 billion a year in extra taxes, with money being poured into schools, hospitals, transport and housing.

But despite Labour’s promises to protect “working people”, a £25.7 billion increase in national insurance contributions paid by employers is likely to reduce wages and lead to job losses.

The overall tax burden will reach a record 38.3% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2027-28, the highest since 1948 as the UK recovered from the impact of the Second World War.

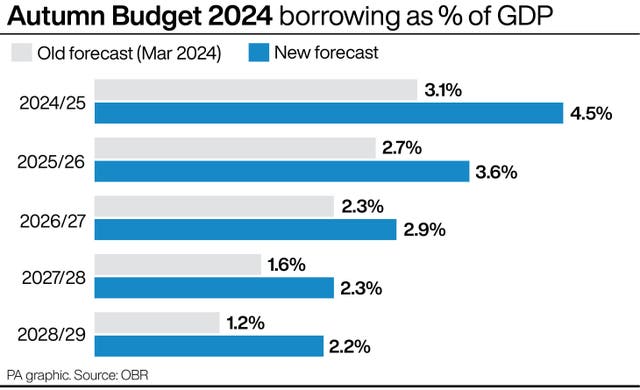

And changing the way government debt is measured allowed the Chancellor greater flexibility to borrow, resulting in what the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) called “one of the largest fiscal loosenings” in recent decades.

Ms Reeves said: “This is a moment of fundamental choice for Britain.

“I have made my choices. The responsible choices. To restore stability to our country. To protect working people.

“More teachers in our schools. More appointments in our NHS. More homes being built.

“Fixing the foundations of our economy. Investing in our future. Delivering change. Rebuilding Britain.”

But Tory leader Rishi Sunak accused Ms Reeves of “fiddling the figures” by changing the debt target, adding: “The reason the Chancellor has increased borrowing and increased taxes is because she has totally failed to grip public spending.”

Paul Johnson, director of economic think tank the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said the Budget would deliver a “short-term sugar rush” for the economy as a result of the “debt-financed spending splurge”.

But “somebody will pay for the higher taxes – largely working people”.

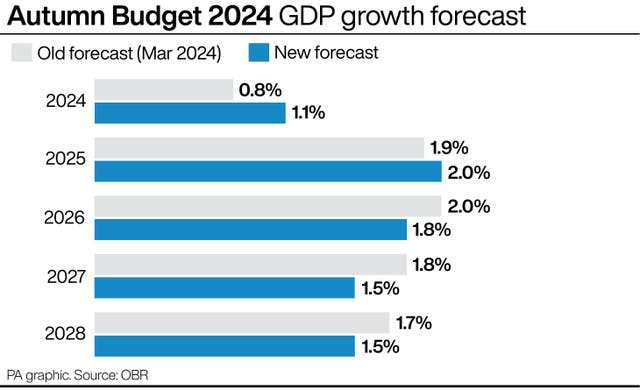

The OBR’s forecast suggested the increase in spending would provide a temporary boost to GDP, upgrading growth this year from 0.8% to 1.1% and from 1.9% to 2.0% in 2025.

But there are downgrades in subsequent years – down from an expected 2% in 2026 to 1.8%, from 1.8% in 2027 to 1.5% and from 1.7% in 2028 to 1.5%.

And the Budget measures will also add to pressure on inflation and interest rates, the OBR said.

The latest OBR forecasts indicate that inflation will rise to 2.6% in 2025 “partly due to the direct and indirect impact of the Budget” – significantly above the 1.5% rate previously predicted.

Higher-than-expected Bank of England interest rates could be the response to control inflation, which would feed into mortgage costs.

Ms Reeves claimed the scale of the public spending problems she inherited were worse than previously thought.

She repeated her claim that a £22 billion “black hole” left by the Tories in this year’s finances showed they “hid the reality of their public spending plans”, with problems recurring in future years.

But the OBR steered clear of using the £22 billion figure in its assessment of the previous government’s figures.

Ms Reeves also promised to set aside £11.8 billion to compensate those affected by the infected blood scandal and £1.8 billion to compensate victims of the Post Office Horizon scandal.

The Chancellor said: “Together, the black hole in our public finances this year, which recurs every year, the compensation payments which they did not fund and their failure to assess the scale of the challenges facing our public services means this Budget raises taxes by £40 billion.”

She confirmed a raid on employers’ national insurance contributions (NICs), with higher rates and a lower starting threshold, raising £25.7 billion by 2029-30.

The rate will increase by 1.2 percentage points to 15% from April 2025, with payments starting when an employee earns £5,000, down from the current £9,100.

“I know that this is a difficult choice. I do not take this decision lightly,” Ms Reeves said.

The OBR forecast that by 2026-27 some 76% of the total cost is passed on through lower real wages – a combination of pay cuts and increased prices.

The measure could also lead to the equivalent of around 50,000 average-hour jobs being lost, the watchdog said.

The Chancellor announced a £2.5 billion increase in capital gains tax by increasing the lower rate from 10% to 18% and the higher rate from 20% to 24%.

She also confirmed changes to inheritance tax, including bringing pension pots within the tax from April 2027, and reducing reliefs for agricultural and business property, raising a total of £2 billion a year.

Labour’s commitment to impose VAT on private schools will raise £1.7 billion by 2029-30, while changes to the energy profits levy and air passenger duty rates rake in £3.6 billion.

The stamp duty land tax surcharge for second homes will increase by two percentage points to 5% from Thursday.

The tax hikes and increased borrowing allow Ms Reeves to provide a £22.6 billion increase in the day-to-day health budget as well as a £3.1 billion increase in the capital budget, which she called the “largest real-terms growth in day-to-day NHS spending outside of Covid since 2010”.

She also promised £1.4 billion to rebuild more than 500 schools along with £2.1 billion for maintenance.

Ms Reeves insisted there would be “no return to austerity”, with departments’ day-to-day spending set to grow by 3.3% in real terms between 2023-24 and 2025-26.

In other measures:

– Income tax thresholds will rise in line with inflation from 2028-29, reducing the impact of “fiscal drag” where rising wages see people pulled into higher tax bands.

– The freeze on fuel duty will continue, including maintaining the existing 5p cut.

– Draught duty will be cut by 1.7%, knocking a penny off a pint in the pub, but other alcohol rates will increase.

Ms Reeves’s Budget was constrained by two self-imposed “fiscal rules” – funding day-to-day spending through taxation, and for debt, measured by the new benchmark of “public sector net financial liabilities”, to be falling as a share of GDP.

On the central forecast they are on course to be met by relatively small margins of £9.9 billion and £15.7 billion in five years’ time.